My Favorite Comparative Literature Master’s Class in Paris: Top Courses & Study Tips

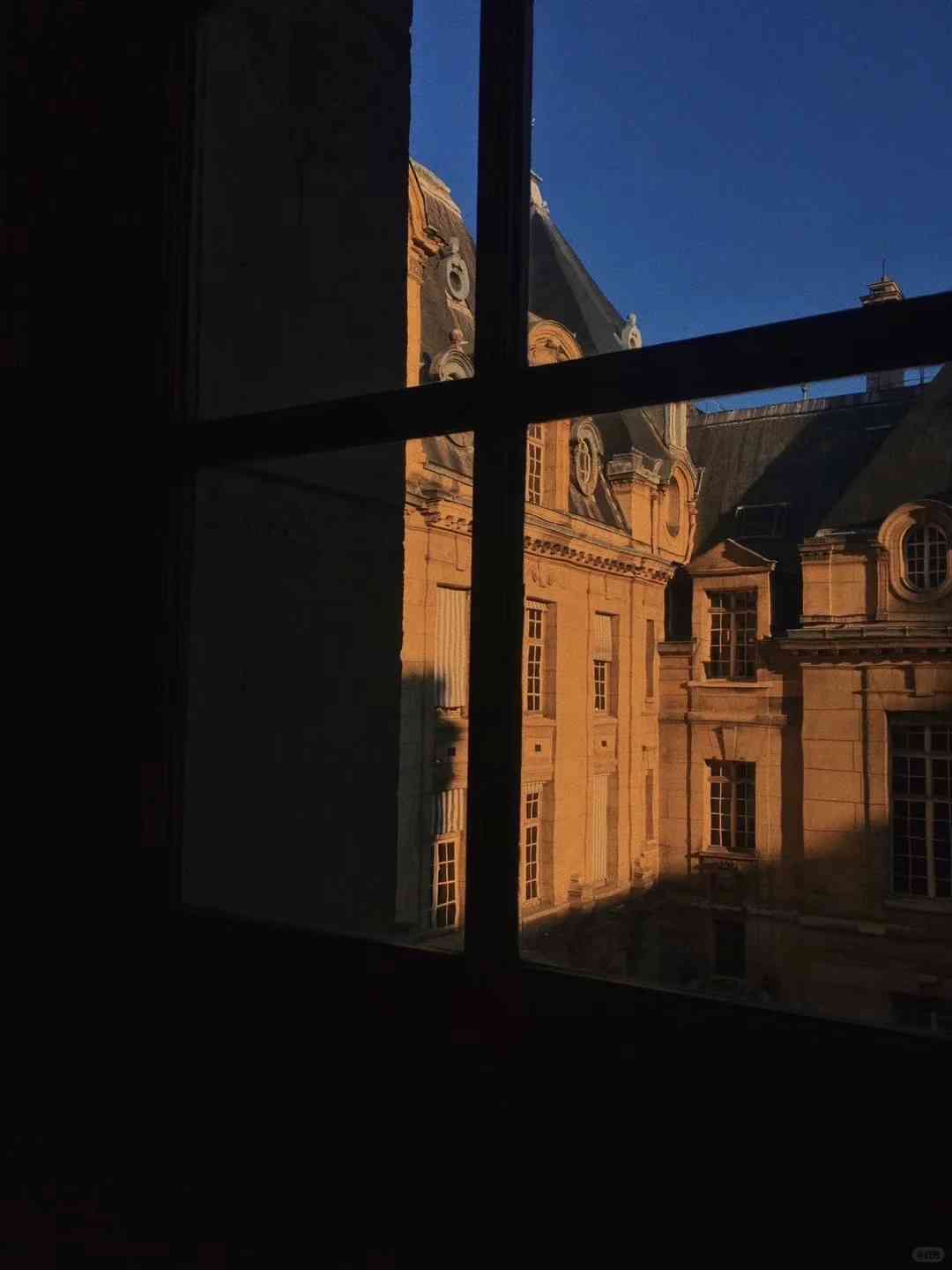

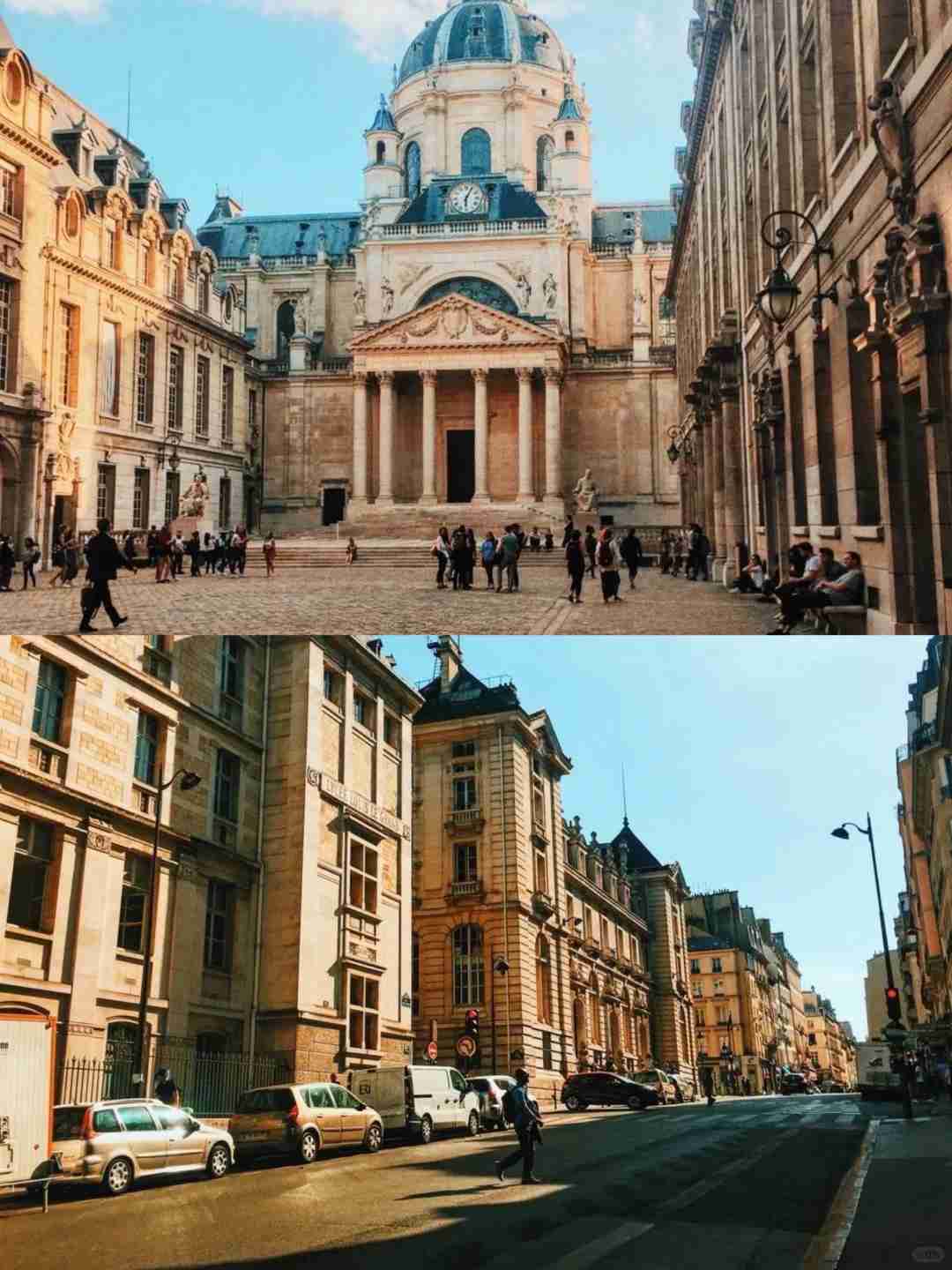

In the Comparative Literature program at the historic Sorbonne University, there exists a fascinating course titled *La démographie des personnages*—exploring the demographic landscape of characters within novels. This class quickly became my favorite, not only for its captivating subject matter but also because each session unfolded within the hallowed halls of a centuries-old building, allowing me to soak in a profound sense of history and academic tradition.

Our instructor was a wonderfully gentle elderly scholar, whose research centered on the comparative study of English and French literature, with a special focus on giants like Balzac and Dickens. Consequently, all the texts we examined were drawn from the rich literary traditions of England and France.

She spoke with a deliberate, melodic cadence, often running out of time before concluding her lectures. Whenever this happened, she would throw her hands up and exclaim, “Help!” in the most endearing way. It was the one class where genuine, shared laughter filled the room every single time.

The course introduced us to web-based statistical tools to dissect various facets of novel characters—such as their numbers, naming patterns, frequency of appearance, gender distribution, professions, birth and mortality rates, and even causes of death. We could filter our analyses by nationality (English versus French), author gender, or specific writers like Balzac or Dickens. Each student selected their own set of novels and spent the semester crafting an original research report.

Through this immersive experience, I uncovered several intriguing patterns.

For example, between 1811 and 1821, English novels saw a noticeable surge in character numbers. This spike aligned with Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo and the subsequent rise in British national pride—showing how literature often mirrors sociopolitical shifts.

Another memorable moment involved the term *enfants* (children), abbreviated as ENF. A specific subcategory, *ENFn* (short for *les enfants naturels*, or “natural children”), prompted an Italian classmate to ask, “What exactly are *les enfants naturels*?” With a playful glint in her eye, the teacher replied, “An excellent question!

After all, we must distinguish them from children raised in laboratories.” The room burst into laughter. In reality, *enfant naturel* referred to “illegitimate children” under early 19th-century civil law—those born outside of marriage.

Realist literature, as this course vividly demonstrated, serves as a powerful reflection of society, embracing an astonishing range of themes. Whether applied to political economy, sociology, demography, or education, it offers a treasure trove of insights waiting to be uncovered.

Five years have flown by since I tossed my graduation cap into the air. Whenever I reminisce about my student days in Paris, my thoughts inevitably wander along those ancient, weathered cobblestone paths—some over eight centuries old—and linger in classrooms where the watchful eyes of French literary giants seemed to follow our every move.

But looking back now, I realize the real magic wasn’t in the textbooks we pored over or the endless essays we penned. It was in those rare, suspended moments when time folded in on itself, wrapping me in a profound stillness. In those instants, I felt it clearly: literature isn’t some dusty artifact confined to history—it’s a living, breathing dialogue that bridges past and present.

The class in the old Sorbonne building felt like stepping into a story itself. Learning about character demographics made literature feel fresh and analytical. The professor’s quiet passion made even dense texts engaging.

The class on character demographics felt like stepping into a living archive. Learning in those old halls made the past feel present. It’s rare to find a course that blends history with literary analysis so seamlessly.

The class in the old building felt like stepping into a story itself. Learning about character demographics in novels was both unusual and oddly fitting. The professor’s calm presence made even dense texts feel approachable.